Never have I loathed a character more than Cathy Ames in John Steinbeck’s East of Eden—and I mean that in a good way. With the book on my lap, I hurled invective at the page and found myself enraged by her two-faced, back-stabbing ways. That a character could elicit such a visceral response is testament to the author’s skill. Needless to say, I’ve long been a devoted Steinbeck fan.

What I love about his work–in addition to the characters and writing–is its deceptive simplicity. There are complex issues at play beneath the surface of his stories, yet he presents them in a way that never clouds the human drama. Cannery Row, with its themes of spirituality, happiness, and being close to nature—among others—appears on the surface to be a charming tale of down-and-outs in Monterey’s sardine-canning district.

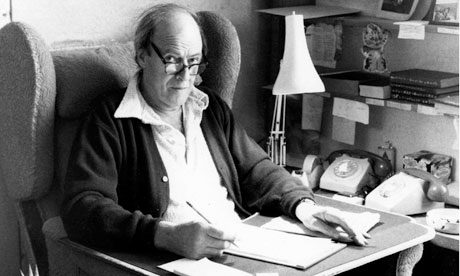

As previous posts here suggest, I’m fascinated by the working habits of my favorite authors and the way they approach writing. Here, from a 1975 article in the Paris Review, are six writing tips from Steinbeck.

It is usual that the moment you write for publication—I mean one of course—one stiffens in exactly the same way one does when one is being photographed. The simplest way to overcome this is to write it to someone, like me. Write it as a letter aimed at one person. This removes the vague terror of addressing the large and faceless audience and it also, you will find, will give a sense of freedom and a lack of self-consciousness.

Now let me give you the benefit of my experience in facing 400 pages of blank stock—the appalling stuff that must be filled. I know that no one really wants the benefit of anyone’s experience which is probably why it is so freely offered. But the following are some of the things I have had to do to keep from going nuts.

1. Abandon the idea that you are ever going to finish. Lose track of the 400 pages and write just one page for each day, it helps. Then when it gets finished, you are always surprised.

2. Write freely and as rapidly as possible and throw the whole thing on paper. Never correct or rewrite until the whole thing is down. Rewrite in process is usually found to be an excuse for not going on. It also interferes with flow and rhythm which can only come from a kind of unconscious association with the material.

3. Forget your generalized audience. In the first place, the nameless, faceless audience will scare you to death and in the second place, unlike the theater, it doesn’t exist. In writing, your audience is one single reader. I have found that sometimes it helps to pick out one person—a real person you know, or an imagined person and write to that one.

4. If a scene or a section gets the better of you and you still think you want it—bypass it and go on. When you have finished the whole you can come back to it and then you may find that the reason it gave trouble is because it didn’t belong there.

5. Beware of a scene that becomes too dear to you, dearer than the rest. It will usually be found that it is out of drawing.

6. If you are using dialogue—say it aloud as you write it. Only then will it have the sound of speech.